Just as REAP Food Group set up shop in its new Garver Feed Mill office in April, 2023, we also welcomed Katie Rozas as our new Development Director. A member of the REAP Board of Directors since July 2021, and once a member of the Development Committee, Katie has an intimate understanding of REAP’s work. Her role will be to oversee and guide a growing portfolio of stewardship efforts including grants management, fundraising events, and donor relations. Whether in the classroom or in the boardroom, Katie is passionate about social justice and environmental protection. Prior to joining REAP, she spent over 15 years in multilingual learner education, strategic communications, and marketing. Katie was introduced to REAP six years ago by her then-four year old daughter who came home describing her new love for jicama sticks, which she tasted during snacktime, thanks to the REAP Farm to School snack program. “I understand firsthand how the REAP mission, vision, and dedication of the organization has made an incredible impact in my community and beyond," Katie said. "I am thrilled to now dedicate myself to extend that impact and ensure REAP secures the funding and resources necessary for its programs and services to grow and flourish for many years to come." “I am thrilled to...

Blog

REAP Food Group is thrilled to announce that this month we are packing our boxes and moving to the historic Garver Feed Mill! Learn more below, courtesy of Garver Feed Mill: The award winning Garver Feed Mill, located next to Olbrich Botanical Gardens, is pleased to welcome their new tenant, REAP Food Group. REAP Food Group, a non-profit organization based in Madison, WI, believes in transforming communities, economies, and lives through the power of good food. Their work centers around creating an equitable, local, and sustainable food system in Dane County and Southern Wisconsin through Farm to School, Farm to Business, and Community Partnership programming. “When Garver Feed Mill contacted me last summer about potentially moving to the space, little did I know this has been several years in the making,” explained REAP Executive Director, Phil Kauth. “As Garver continues to find innovative ways to support the local food system, we are incredibly excited to bring our work assisting in creating a more equitable food system straight to them.” While REAP will be the first nonprofit to grace Garver’s brick walls, it will join an impressive roster of fourteen other entities specializing in food production and food systems, health/wellness and hospitality including Kosa KOSA Ayurvedic Spa & Retreat, Garver Events, Ledger Coffee Roasters, Twig & Olive Photography, Glitter Workshop, Nessalla Kombucha, Sitka Salmon Shares, Ian’s Pizza, Calliope Ice Cream, Perennial Yoga, Clouds North Films and Roll Play Madison. Throughout the year, Garver also hosts several food-oriented events include the Late Winter Dane County Farmers Market, Farm to Flavor and Femmestival, a festival that celebrates and uplifts womxn, femmes and nonbinary entrepreneurs, artists, and food producers. The Feed Mill, once a massive beet producing factory was converted to a feed mill in 1931 and achieved landmark status in 1994 as an important surviving link to the agricultural industry in the Madison vicinity. "In a poetic sense, the buildings historical connection to the region’s agriculture economy has come first circle with the businesses inside Garver and the organizations like REAP and Dane County Farmers Market doing the incredible and import work to create a healthier, more sustainable food system” says Bryant Moroder, a member of the Garver Redevelopment Team. “The timing of the move is perfect for REAP,” continued Kauth. “Not only is the space inviting, but the possibilities for REAP to collaborate to host and participate in community events at Garver will help us fulfill our mission to transform lives through the power of healthy, local food.” ...

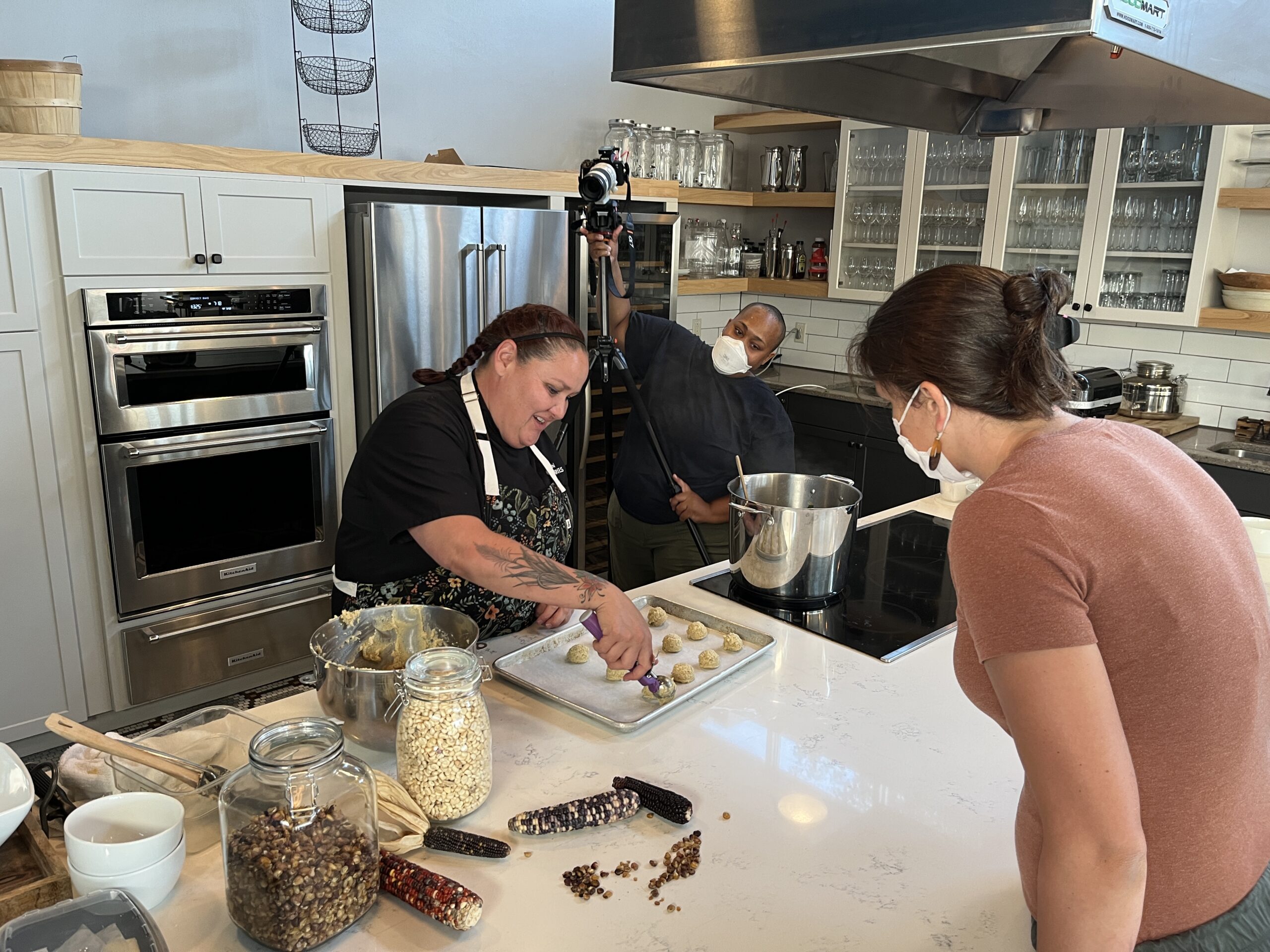

A partnership between Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Food and Nutrition and REAP Food Group spent much of 2022 bringing local agriculture straight to classrooms thanks to a USDA Farm to School grant. The Harvest of the Month program includes Virtual Farm Tours and a series of video shorts featuring vegetables that students will find right on their lunch trays! In Spring and Fall of 2022, REAP Food Group led virtual farm tours across southern and southwest Wisconsin with help from Shiftology Communications. K-5 classrooms across Madison public schools zoomed into the tours and asked farmers questions live, while REAP polled classrooms to find out how many varieties of apples or mushrooms students could name, or what they thought CSA stood for (= Community Supported Agriculture). Meanwhile, REAP brought on independent video producer Bria Brown, based in Atlanta, GA, to produce engaging short films featuring peppers, greens, corn, and cucumbers. Together Brown, Farm to School Director Allison Pfaff Harris, and Communications Manager Samantha Kincaid visited several local growers and food makers over the summer of 2022 to collect stories and footage. I was repeatedly amazed by all that can be grown in compact spaces and places.Allison Pfaff Harris, REAP Farm to School Director Over the lifetime of the grant, the team got to share the inspired voices of farmers who often spend their days deep in manual labor and managing teams both tiny and large. [O]ne of my takeaways was that farmers are very forthcoming with their knowledge, and want a place to share what they do. These tours provided the opportunity for farmers to share their work and knowledge on a larger platform, without having to leave their farms," said Farm to School Director, Allison Pfaff Harris. All tours and vegetable videos are available for public viewing at the Harvest of the Month page. A Special Thank You to the farmers and chefs who contributed their time and passion to this grant: Alex Booker, Badger Rock Urban Farm and Booker Botanicals Armando Pérez, Pérez Produce Bethanee Wright, Winterfell Acres Elena Terry, Wild Bearies Heidi and Julian Zepeda, Tortilleria Zepeda John & Halee Wepking, Meadowlark Organics Liz Griffith, Door Creek Orchard Patty Grimmer and Ky Christenson, Wonka’s Harvest Sarah Leong, Squashington Farm Tommy Stauffer, Vitruvian Farm Yimmuaj Yang, Groundswell Conservancy Yusuf Bin-Rella, Trade Roots Culinary Collective ...

Noah Reinkober, a student in the UW Madison School of Human Ecology, joined us this fall as a Farm to School intern, supporting Director Allison Pfaff Harris and REAP's partnership with MMSD Food and Nutrition. The following article was researched and written by Noah. Many people today are familiar with the concept of a “food desert," not just those in academia or the fields of sociology and human ecology. The term, which began being used in the 1990s, refers to a neighborhood, often in an urban environment, which has very little access to food. People living in a food desert may have restaurants in the area, but have to travel far to purchase foods at a grocery store, or they may simply be lacking in nearby food entirely. As the understanding of this issue has progressed over the last few decades, activists and researchers have proposed different labels for these areas. “Food swamp," a term which came into usage about a decade ago, refers to the same areas, but emphasizes the fact that these neighborhoods are often saturated with unhealthy foods, rather than lacking food entirely. Both of these terms are misleading when it comes to the conversation about food access, however. Deserts and swamps, unpleasant as they’re often perceived to be, are natural parts of the global environment with unique and thriving ecosystems. Neighborhoods which are deprived of healthy food options are not naturally occurring. To better describe this phenomena, Karen Washington, a Black farmer, activist, and organizer, came up with the term “food apartheid.” Rather than labeling a lack of food access as a natural occurrence, Washington’s term explicitly states the role that politics, economics, and histories of classism and racism play in the matter. Food apartheid occurs when institutions fail to invest in communities which need the investment the most. Food apartheid occurs when institutions fail to invest in communities which need the investment the most. Segregation, poor public transportation, redlining, high food prices, lack of access to growing land, and perceived lack of profitability for private businesses are just a few examples of things which inform food apartheid, all of them products of society, not nature. Karen Washington grew up in New York City, so that is the context from which she is working, but the systemic racism and classism which created food insecurity in NYC exists in Madison, WI too. According to Nicholas Heckman, a Public Health Planner in Policy and Food Security in Madison, because of how new the concept is, food apartheid “hasn’t yet been effectively measured at the local level.” Rather, data around food access and food insecurity often comes from the state or county, and researchers must use “various proxy data points and population characteristics to draw conclusions.” Though now dated, and lacking the context of COVID-19, Heckman’s 2016 report, Hunger and Food Security in Wisconsin and Dane County, sheds some light on the disparities which exist on the state and county levels. In 2016, it was reported that 12.4% of all people in Wisconsin, and 11.8% in Dane...

On Tuesday, May 24, REAP Food Group, in partnership with Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Food and Nutrition, zoomed into classrooms for our second Virtual Farm Tour, this time with farmers Patty and Ky of Wonka's Harvest in Hollandale. Geared to grades K-5, the live presentation included an experiment demonstrating the benefits of no-till agriculture using various soil mediums. Patty and Ky answered questions from students about the favorite crops they grow, and they shared their love of bees. Watch a recording of the tour, and consider following Patty and Ky's lead and improve your own garden soils with compost! Virtual Farm Tours are made possible through a grant and brought to classrooms by REAP Food Group, in partnership with Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Food and Nutrition in an effort to deliver the sights and smells of Wisconsin-grown foods to MMSD classrooms through virtual farm tours, videos, and books. Shiftology Communication Virtual Farm Trips® facilitated the tours. The unique PR firm offers "one-of-a-kind learning experiences by connecting participants to real working farms from the comfort of their computers, classrooms, conference rooms and living rooms." https://youtu.be/hmk7bahUJCQ ...

On Thursday, May 5, REAP Food Group, in partnership with Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Food and Nutrition, zoomed into eighty-three classrooms for a Virtual Farm Tour at Vitruvian Farms in McFarland. The tour marked the first in an ongoing series to deliver the sights and smells of Wisconsin-grown foods to MMSD classrooms through virtual farm tours, videos, and books. Geared to grades K-5, the live presentation included a tour of the farm led by co-owner Tommy Stauffer*, poll questions for the nearly 1,500 students gauging their knowledge of, and like--or dislike--of mushrooms, and a Q&A for Tommy. Hosts discovered that the students already had a rich vocabulary in mushroom varieties, and were at least amenable to tasting them! Watch a recording and stay tuned for the next tour at Wonka's Harvest in Hollandale before schools close for the summer. Virtual Farm Tour is made possible through a grant and brought to classrooms by REAP Food Group, in partnership with Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Food and Nutrition. Shiftology Communication Virtual Farm Trips® facilitated the tour. The unique PR firm offers "one-of-a-kind learning experiences by connecting participants to real working farms from the comfort of their computers, classrooms, conference rooms and living rooms." *Tommy Stauffer is also a REAP Food Group board member. https://youtu.be/FxqWG0x0Mgs ...

REAP Food Group's staff and board are thrilled to welcome Philip Kauth as our new Executive Director. After earning a Ph.D. in Horticultural Sciences, Phil spent eight years working with the Iowa-based non-profit Seed Savers Exchange. As Director of Preservation, Phil led a team that stewarded a living collection of 25,000 open-pollinated seed and plant varieties and a historic apple orchard. With Seed Savers Exchange, Phil's work fused his scientific training with the organization's mission to preserve and share seeds, their integrity, and culturally significant stories. "For communities to have control over their foodways, they need to have control over the seeds they want to grow and share," Phil explains. In pursuit of REAP's mission to make healthy food grown well, accessible to all, and in a manner that honors communities' agency over their foodways, Phil brings open ears and a collaborative spirit. He embraces a leadership style that emphasizes learning and building trust to maximize the values and strengths people bring to the table, and he draws from experiences partnering with historically underrepresented groups. Phil’s work with Seed Savers Exchange has included collaborations with Asian American farmers on the West Coast searching for linkages to ancestral food crops, the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network to restore seeds to tribal communities, and the organization's multi-disciplinary collaboration, the Heirloom Collard Project. “REAP has exciting times on the horizon and happily welcomes Phil Kauth to lead the organization into the future[.]...

We are thrilled to announce that Madison Community Foundation (MCF) has awarded REAP Food Group a $50,000 Community Impact Grant to expand our development and fundraising capacity. We will use the funds to hire a grant writer and train our board of directors in fundraising skills in order to grow support for our efforts to build a sustainable and just local food system. COVID-19 laid bare for REAP the unreliability of in-person events as fundraising drivers. Meanwhile, it presented an opportunity to collaboratively problem solve with community partners on the ground. In 2020 we co-created the Farms to Families Fund with Roots4Change to get food into the hands of families who needed it. The impact we saw from that collaboration showed us that we have even more work to do in the community. A focus on strengthening our development capacity in the immediate future will allow REAP to focus our energy into our core goals and on mission-oriented events without relying on restaurant partners to donate time and resources, especially as the food service industry deals with challenges exacerbated by a pandemic. We have big dreams to realize in our efforts to expand Farm to School programming beyond the Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD), to plan for future disruptions in our local food and farming value chain, and advocate for policies that support sustainable agriculture and a fair food system. “REAP is taking a strategic approach to long-term financial sustainability, recognizing the importance of using not just the development director but also the executive director and board members to build a strong culture of philanthropy[.]...

Free school meals pack a punch. They improve students’ learning readiness, behavior, and health outcomes, address racial disparities, eliminate stigma around free and reduced school meals, and support working families. They also have the potential to strengthen our local economy by creating jobs and bolstering our local agriculture. The fate of free school meals, meanwhile, faces a reckoning. When COVID-19 forced the closure of schools and childcare providers nationwide in March 2020, the USDA changed the rules governing access to school meals. They ripped away bureaucratic layers and among other moves, made free, healthy meals available to all students, regardless of financial need. As the June 2022 expiration date for universal free school meals approaches, Wisconsin State Representatives Kristina Shelton and Francesca Hong, State Senator Chris Larson, and WI State Superintendent Dr. Jill Underly have introduced the Healthy School Meals for All Act (LRB 4605), which would permanently provide state aid to reimburse public and private schools that provide free meals to all students for the costs of those meals. "[W]hat must be our core value in Wisconsin is that no child should go hungry because a guardian in their life cannot afford a school meal."Rep. Francesca Hong “As a mom, chef and legislator I know first-hand the importance of building community through food. And what must be our core value in Wisconsin is that no child should go hungry because a guardian in their life cannot afford a school meal. All across this state, from our farmers and teachers to our students and school staff, we have learned that we must provide our children with more support during the school day,” Rep. Hong explained in a press release. REAP supports the Healthy School Meals For All legislation, and we hope you join us in raising our voices for healthy, reliable school meals for all by contacting your legislators today. Learn more about the bill at the Healthy School Meals for All Website and find additional tools for helping spread the word through the School Nutrition Association. ...

Dear REAP Friends, We are all still cheering over a strong year-end campaign, excited that countless hours of deliberation on how to grow and deepen our impact is starting to come to fruition and that your support and investment means we hit the ground running in 2022. In that context, there is another big change coming: this spring, I will be moving on after serving as the Executive Director of this vital community organization for the past five and a half years. My family has an opportunity to temporarily relocate overseas, and as we see the window of time as a family of 4 get ever-smaller, we feel this was the right time to take the leap if we do this together. It has been a true honor and deep privilege to learn, listen, work and celebrate with so many smart and passionate people who choose to work to make the world a better place. Given the scale of our global - and local - problems, it’s tempting to give in to cynicism, maybe too easy to convince yourself you can’t do anything about it. And yet, every single day, I am surrounded by caring, creative humans who - to quote Theodore Roosevelt - step into the arena and dare greatly to rise to the challenge of dismantling racism, rebuilding a just food system, reversing environmental destruction and co-creating the community that reflects our diversity and shared values. And as I listen to the conversations of my own young teens, I feel even more hopeful that we are in good company with the next generation of changemakers coming our way. REAP is doing important work at the nexus of food systems, social justice and environmental protection and we are seeking that next dynamic leader to harness the momentum, continue to forge deep partnerships and lift up the ridiculously talented team at REAP who serve farmers, children, chefs, and food businesses and dare greatly every day to build a just and sustainable local food system. Maybe you know that person? Maybe you are that person? I couldn’t imagine a better place to land, or a better time to be joining REAP. And I look forward to joyously writing those checks, attending farm dinners and contacting elected officials as a proud member of REAP Food Group. The position description is posted on our website, please help us spread the word. Yours truly, Helen Sarakinos ...

- 1

- 2